By CHUCKIE MAGGIO

When the son he called a “mama’s boy” became one of basketball’s greatest centers, Robert Lanier Sr. imparted a nugget of off-court advice.

“I told (Bob) never to refuse to give a kid an autograph,” Lanier Sr. told La Crosse Tribune sportswriter Jay Loeffler in 1980. “Once during an autograph session there were about 300 kids waiting for an autograph. His secretary told him to sign a piece of paper and she would run them off a copier. He said no way. Most players wouldn’t do that.”

It’s ironic, then, that the signature Bob Sr. implored Bob Jr. to turn down changed St. Bonaventure basketball history.

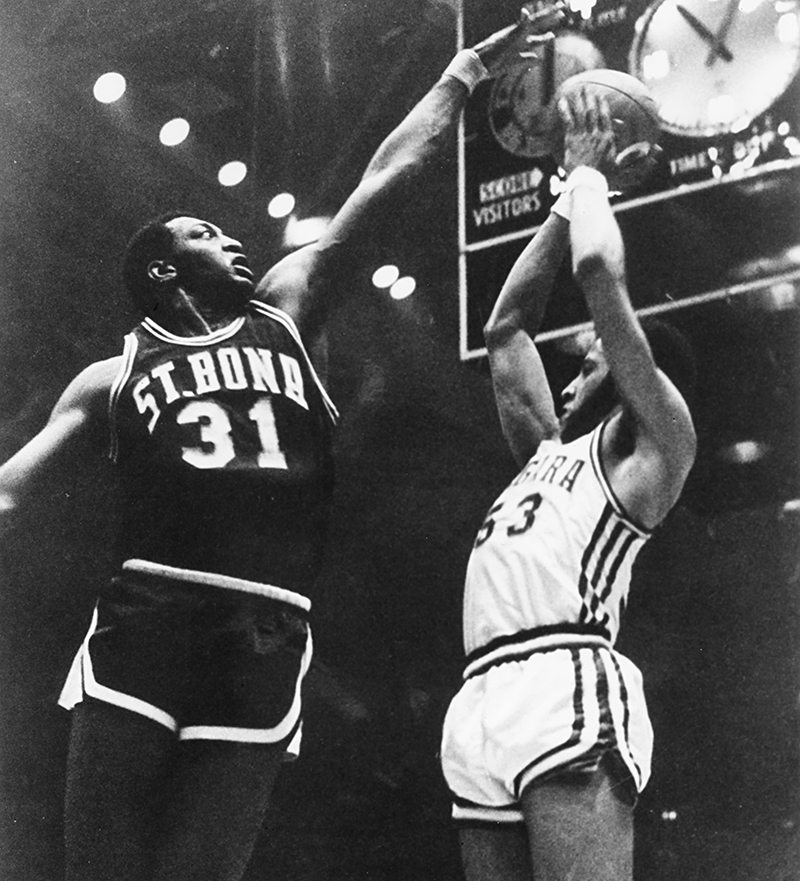

Bona’s designs on a postseason appearance in the 1968-69 season were dashed by NCAA recruiting sanctions resulting from the pursuit of eventual South Carolina commit Tom Riker. The team started 3-5, marked by a four-game losing streak. SBU regrouped by winning 14 of its last 16 games, routing No. 18 Marquette by 22 in New York and dispatching Canisius by 27 at the Buffalo Memorial Auditorium during that run.

Bonaventure was convinced that with core players like Lanier, Dale Tepas and Billy Kalbaugh returning for 1969-70, it could make a national championship run. The Brown Indians had competition, however, in the form of a $1.2 million offer for Lanier to forgo his final year of eligibility and go pro.

The New York Nets were the laughingstock of the American Basketball Association in 1969, patching together a woeful 17-61 record and falling 19 games behind the second-to-last Minnesota Pipers in the ABA’s Eastern Division. With the league’s worst offense and a defense that allowed 117 points per game, just 249 fans showed up at Commack Arena for the Nets’ Christmas Day game against the Denver Rockets.

Lanier was fresh off averaging 27.3 points and 15.6 rebounds per game as a junior. If he weren’t playing at the same time as “Pistol” Pete Maravich, the most prolific scorer in college basketball history, and Lew Alcindor, the most decorated winner in college basketball history, he may have been the most sought-after amateur player.

New York owner Roy Boe, knowing the paltry attendance his games garnered that season was not sustainable, desperately needed a star. The Nets approached Lanier, offering him a $1 million contract.

The ABA was in many ways the NBA’s equal, with stars like Rick Barry, Mel Daniels and Connie Hawkins. The NBA did not explode in popularity until the 1980s, after the 1976 ABA-NBA merger; Finals games were even relegated to tape delay. Lanier was tempted, as any college player would be, by the lucrative offer.

Bob Sr. was unimpressed. “Stay in college and get your degree,” he remarked. “I know you’re going to be a superstar, but I don’t want you to be a dumb superstar.”

Lanier’s affinity for his father made staying one more year a foregone conclusion. Bona celebrated the 50th anniversary of father knowing best this year; Lanier led his 1969-70 squad to 25 wins in 28 chances and the lone Final Four appearance in school history.

The Buffalo native indeed became a superstar, and his father watched him spurn the Nets a second time ($2 million this time) that spring to sign a five-year deal with the Detroit Pistons after they selected him No. 1 in the NBA Draft.

“The indications are that we have lost him,” said Boe, whose Nets tenure ended tumultuously when financial troubles forced him to sell Julius Erving to Philadelphia in 1976 after three seasons and eventually sell the team in 1978.

No one will know for sure if Lanier would have reversed the franchise’s fortunes and prevented fans from bringing banners that read, “A Tisket, a tasket, put Boe in a casket.” But the “Dobber” surely couldn’t have hurt matters.

The bond the Lanier family shared made Lanier Sr.’s death in a 1980 hit-and-run accident all the more devastating.

Police said Lanier Sr., still living in Detroit as a sales representative, was stopped for driving 55 in a 45-mile-an-hour zone and had his van impounded because of an outstanding warrant from 1977. The officer told Lanier Jr., who learned the news at LaGuardia Airport in New York after the Bucks played the Knicks, that his dad declined a phone call because it was midnight and he didn’t want to disturb anyone.

Instead his dad walked, “in the middle of never-never land” as Lanier Jr. described it to the Detroit Free Press, and was killed in Waterford Township near Pontiac Mall.

Ira Berkow described Lanier Sr. and Jr. as “more like brothers than father and son” in the New York Times. “They played poker together, they argued, they enjoyed each other.”

“Pops in his way always tried to make things easier for me,” Lanier told Berkow. “I grew fast as a kid and being so big – 6-foot-8 by the time I was 14 – you feel insecure. You always feel awkward. Normal clothes don’t fit. I’d have to wear sloppy big man’s clothes. I’d go to a party and stand in a corner and wouldn’t dance because I thought everyone was staring at me.

“Pops joked about how big I was. He’d say to people that he’d be in the living room when I was in the kitchen and he’d still trip over my feet. From anyone else it would have hurt but from Pops I knew he cared.”

Lanier Sr. was always proud of his only son. When Lanier Jr. was inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in 1992, 28 years ago last week, he knew his father would have treasured the moment.

Bonnies fans will always treasure both Bobs, the younger Lanier for leading them to college hoops glory and the elder Lanier for the advice that shaped 1970.

I loved Bob Lanier. After reading about his life I admire the man he became outside of basketball.