By BILLY HEYEN

ENDICOTT, N.Y. — Hunter Walsh couldn’t throw on Monday or Tuesday. He’d thrown more than 100 pitches in three-straight postseason starts, and he was worried about his chances of throwing in the state final four.

Apparently, Walsh didn’t need to worry about simply throwing. More pressing on Saturday was whether he’d allow a hit. He didn’t, and it was the McQuaid senior who couldn’t throw earlier this week being chased near the mound with water bottles in celebration.

“Perfect timing for it, right?” Walsh said afterward.

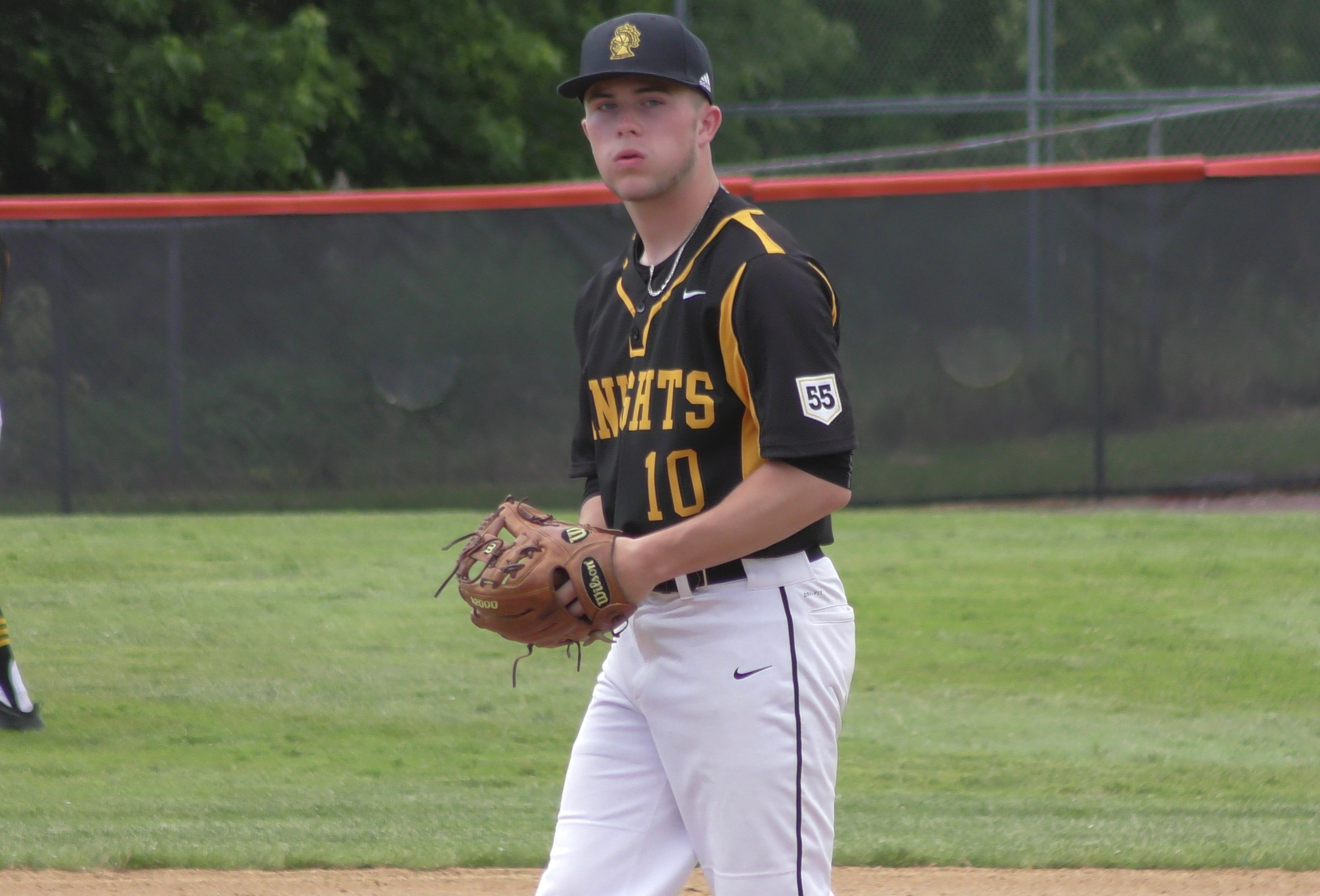

McQuaid baseball won its first-ever state title on Saturday at Union-Endicott High School, 5-0, over Section II’s Shenendehowa. The Knights were led by a no-hit, one-walk, 70-pitch outing from Walsh, the first no-hitter of his life. They were aided by timely hitting from Ben Beauchamp and Patrick Xander. Plenty of great players have worn the white, black and gold of McQuaid. None before had ever climbed to the top of this mountain.

“Best ever,” McQuaid coach Tony Fuller said of this McQuaid team. “First state championship. When I took over four years ago, this was the goal. Didn’t know how long it would take. These guys solidified themselves as the best team ever to put this uniform on.”

Walsh’s dominance throughout the postseason was hard to miss. Entering Saturday, he had three complete games and two runs allowed. But it’d taken its toll by the start of this final week of Walsh’s high school career as he felt pain on the inside of his shoulder. Walsh wrestled with the possibility of not getting to pitch one more game.

“Honestly, it sucked,” Walsh said. “It was like, wow, why couldn’t this wait a week?”

All week, Walsh did everything he could to get ready, hoping the Knights could get to Saturday, and that he’d be available. Stretching, massages, painkillers. By Wednesday, he could toss lightly.

Walsh threw a flat-ground bullpen session on Friday before McQuaid played its state semifinal, and his arm felt better than it had all week. Not good, but better. Fuller didn’t turn to his ace in a tight, late-game spot Friday, hinting at some remaining uncertainty.

So back in the hotel Friday night, catcher Ben Beauchamp rooming with Walsh, the work continued. McQuaid’s trainer spent time with Walsh. Knights’ senior Tyler Griggs remembered an ironic phrase uttered by Walsh during that time with the trainer.

“Our trainer was stretching him out last night,” Griggs said. “And (Walsh) was like, ‘I might throw a no-no tomorrow,’ just like joking around. And it happened.”

Before Walsh took the mound for each of his seven innings, he extended his right arm toward a McQuaid assistant for it to be shaken out. By the time his cleats toed the rubber, Walsh looked no different than he had all postseason.

Fastballs to the outside corner, again and again, Walsh’s preferred spot to throw and Saturday’s home plate umpire’s preferred spot to be generous. If Walsh was ever going to make it through a complete outing, he’d need to limit his pitches.

Nine-pitch innings in the first and second helped that cause. So did three McQuaid runs across the first three innings, allowing Walsh to pitch with a lead. The Knights scored in the second on RBIs from Zach Lee and Patrick Xander, then one driven in by Drew Bailey in the third.

Walsh threw 10 pitches in the third, then six more in the fourth, giving him 34 pitches through four frames.

“Once I was up there getting in my zone, no one could stop me,” Walsh said. “… It was perfect timing for me to throw like an 80-pitch game and not a 120-pitch game.”

The McQuaid fielders were aware of what Walsh was doing. An umpire was talking to Noah Campanelli about it as the McQuaid shortstop tried to silence him. When Campanelli bobbled a ball with two outs in the fifth, there was still a perfect game to preserve. But he unleashed a rocket throw, what Campanelli called a “pure frustration” hurl across the diamond, where Charlie Merkley picked it to keep the magic alive.

Walsh was inches from perfection, as it turns out. On a 3-2 count with one out in the sixth, a fastball missed a bit down for a walk. It was Shenendehowa’s only base runner.

“For him to come out there and throw a no-hitter like that, that’s absolutely incredible,” Beauchamp said. “I love that kid more than anything.”

The Knights had tacked on two more runs in the fourth, via a Lee run on a wild pitch and a Beauchamp RBI double. So before the seventh, when Walsh fixed his cap, put his glove in his right hand and strolled toward the mound he’d made his, McQuaid led 5-0. Three outs away from two firsts on the same day.

Groundball to Campanelli, a ball Griggs worried would catch the infield lip and bounce past the shortstop. No such problem, one out. Then a flyball to earlier defensive replacement Jack Beauchamp in left, who raced in to snag it, two outs. Then on Walsh’s 70th pitch, his first to the 22nd batter he faced, a grounder to Campanelli’s backhand side. A throw across the diamond. A no-hitter. A state title.

“I’m gonna remember that forever,” Campanelli said. “Before balls and proms, coach Fuller reminds us that you’re not gonna remember these. You’re gonna remember winning right here. And I think he’s right. I think I’m gonna remember this forever.”

Teammates raced toward Walsh, looking to get him wet with water bottles they opened in the dugout before the last batter. But Walsh spun out of the mob and met his catcher Beauchamp near first base. They embraced, then Walsh let out a scream as tears filled Beauchamp’s face.

Earlier in the week, Walsh’s mother, Bethann, had allowed herself to envision the possibility of a state title. But never did she imagine a no-hitter from her son in the middle of it. Afterward, she couldn’t stop smiling.

“He was spot on,” Bethann said. “I saw that first pitch today, and it was a strike, and then he went out for the second inning, first pitch is a strike. I said, ‘My boy is on today.’ … It’s unbelievably crazy.”

It was obvious, too, what Walsh’s effort meant to his teammates. First, when the state representative went to hand the plaque to Fuller, the head coach pointed for his team to take it. And in that moment, one voice made sure who’d be first to touch it: “Grab that sh*t, Hunter,” a Knight said.

Walsh’s right arm, which had given everything it had, let his left arm do this one, final job. He took the wooden plaque, featuring a golden outline of New York state in the center, and raised it to the sky. This time, he was right in the center of one final, joyous McQuaid mob.

“We’re a family here,” Walsh said. “And I couldn’t ask for a better group of guys to do this with.”

Leave a Reply