By PAUL CIFONELLI

Baseball is a numbers game. Baseball has always been a numbers game. As the game has progressed, so have the type and amount of numbers used. The one thing that has not changed is that players are sometimes evaluated strictly by the statistics they produce.

The best hitters in the early-1900s were those with high batting averages and RBI totals. Once the home run became popular in the mid-1900s, run prevention became essential and earned run average (ERA) and walks and hits per inning pitched (WHIP) came into play. The late-1900s had more all-or-nothing approaches from both hitters and pitchers. Players with the most home runs and strikeouts became the stars of the game, a trend that continues into today.

In 2003, author Michael Lewis published “Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game.” The book, which was turned into a movie in 2011, chronicled the 2002 Oakland A’s and the team’s unconventional process of acquiring players. Oakland was and is notoriously frugal and needed to replace its best players it could no longer afford. The team took an analytical approach to roster construction, using analytics and sabermetrics to find the best players for minimal value. The A’s turned that into a division championship and postseason berth despite spending just over $40 million on its major league team, according to USA Today’s player salary database. According to the same database, the New York Yankees’ four highest paid players in 2002 made over $48 million. The Yankees also made the playoffs that year.

Since Oakland’s success using “moneyball,” nearly every other major league team has attempted to employ it in one way or another. Whether it is a team cutting costs and thinking for the future at the cost of being bad for a few years or getting multiple players who excel at one or two skills instead of paying for a star, MLB teams have been taking ideas and concepts from the A’s since 2002.

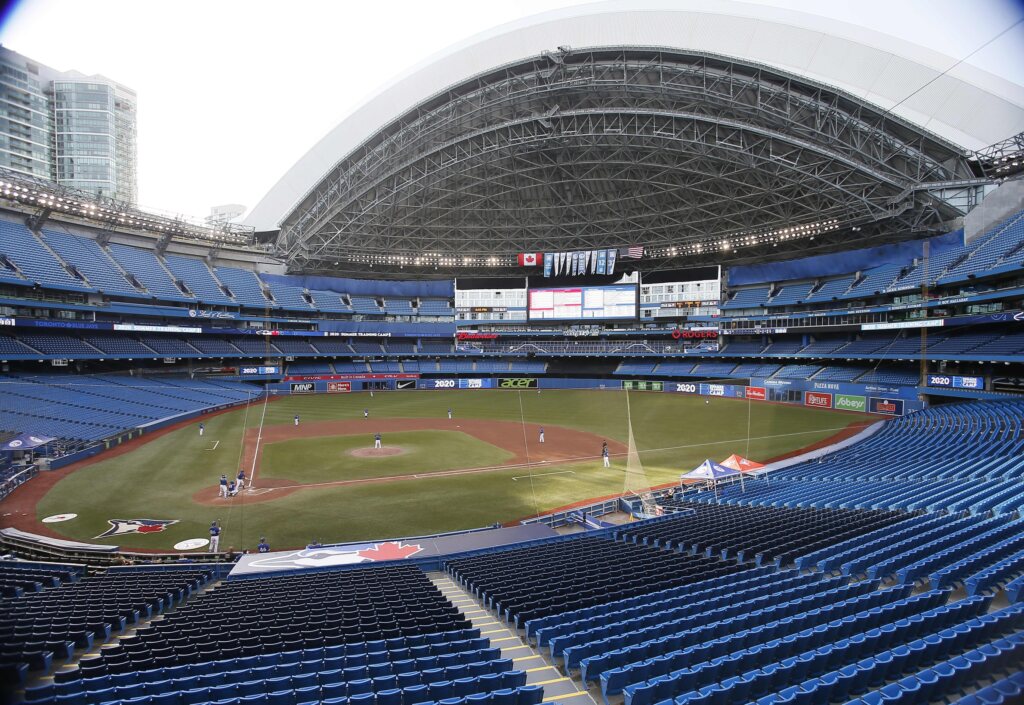

Two teams who have taken different approaches to team building in recent years are the Toronto Blue Jays and the Philadelphia Phillies. The Blue Jays made their first playoff appearance in four seasons in 2020 with a relatively young roster. Toronto has 14 players on its 40-man roster under the age of 25, while only five players on the team have had their 30th birthday. The Phillies, on the other hand, have been big spenders in free agency in recent years despite not making the playoffs since 2011. Philadelphia has 16 players under 25 years old and five 30 or older, similar to the Blue Jays.

The difference in the two clubs is how they spend money. Both have had minimal success in the last five years and have very similar roster construction, but the Phillies’ 2020 payroll was seventh in the league at $80.893 million, according to Spotrac. Toronto spent $54.997 million, about $6.2 million less than the MLB average. Philadelphia’s highest paid player is outfielder Bryce Harper, who signed the largest contract as a free agent in MLB history with a 13-year, $330 million deal. The Blue Jays’ biggest earner is pitcher Hyun-Jin Ryu, who is there on a 4-year, $80 million contract.

This disparity in money spent between two teams in similar situations could come down to one of two possibilities. Either the team has a lot of financial flexibility or they are actively trying to keep payroll low by using “moneyball” techniques.

Two years ago, the same offseason Harper’s contract was signed, Phillies owner John Middleton said the team had money to spend, according to NBC Sports Philadelphia.

“We’re going into this expecting to spend money,” Middleton told USA Today at the owners’ meetings. “And maybe even be a little bit stupid about it. We just prefer not to be completely stupid.”

While Toronto has not been going out and spending crazily like Philadelphia, the 2020 offseason may be different. However, to get here, the Blue Jays made more short-term signings for players who did not require much money.

Sanjay Choudhury is the Blue Jays’ assistant director of research and development. He was hired by the organization at the beginning of the 2016 season, the last time Toronto made the playoffs before this year. Choudhury helps with talent evaluation, whether it is for players to sign in free agency, players to select in the upcoming draft or players who will be facing the Blue Jays in the coming days. While the organizational shift from contending to rebuilding seems like it should have changed his job and how the organization looked for players, it did not.

“The organizational strategy changes and the way you approach things changes, but a lot of my job is still, ‘Do you think player A is better than player B?,” Choudhury said. “Whether you’re a win now team or a win in three years team, you still have to get that decision right. We signed a player in 2017 we knew he wasn’t going to impact our major league team that year. That’s a decision that ended up having ramifications two years down the road, three years down the road and hopefully for our team for a few more years depending on if he’s able to sustain that level of play he’s had.”

When looking for players to sign, management used to rely heavily on professional scouts’ opinions from watching games. Some basic statistics that were attainable were used, but scouts were held in high regard. Now, with advanced metrics and analytics available at the click of a button, many people likely assume that scouting is dying. Choudhury says that is not the case.

“Maybe 20 years ago, before I was involved in the game, you had the ‘nerds’ who were just looking at performance,” Choudhury said. “Scouts sometimes are very heavily invested in subjectivity and things that are more difficult to quantify. I actually think that those two roles, in terms of how you evaluate players, are closer together. Where someone in my position is expected to be able to evaluate players subjectively and also be able to think about how to quantify things like athleticism and makeup.”

With scouts and analysts working so closely together now, both have a seat at the table with the decision-makers when it comes time to build the roster. Choudhury said that player transactions are not taken lightly and everyone who has valuable information on a player is allowed to present it before a decision is made.

“We have a group of people who give their opinions,” Choudhury said. “It’s not a small group because [Blue Jays general manager] Ross [Atkins] is someone who’s very collaborative and very open-minded and wants to get all the different opinions and viewpoints. It’s going to be 15 people or more who are all going to weigh in, all going to see where they’re at.”

Alex Nakahara is the Philadelphia Phillies’ senior quantitative analyst. His job is similar to the one Choudhury has with Toronto except he works a lot more on the day-to-day analytics that will be useful on gamedays. The data that is used goes through multiple departments before it is ready to be analyzed and broken down.

“Our process in a normal year is that the research and development staff create a lot of the models and produces things for the day-to-day,” Nakahara said. “Then the advanced scouting analysts do the running of the models and look at the results and look at each individual opponent and see how they want to tailor it and customize it.”

From there, analysts like Nakahara will look at the models and determine what the numbers mean and why they came out that way. In a year where COVID-19 is not limiting the number of people at a facility, Nakahara and the coaching staff would have conversations about the data from time to time to see what things they could change on the field or if something in the data seemed inconsistent with what was happening on the field.

Nakahara also mentioned that he does not have conversations with players about the data he breaks down. He has those conversations with the coaching staff and lets the coaches relay the data to the players.

When creating the models and breaking down the results, it yields things that can be done in certain scenarios. Seeing those results play out on the field can make the job rewarding, but Nakahara said there is also a downside to running so many tests.

“There definitely are fun aspects of it, especially the creative brainstorming part of it,” Nakahara said. “There are some downsides, like we came up with 20 ideas but when can we do all of them? It’s just not possible to do all these different things. Sometimes you can have too many ideas.”

It has always been impossible to watch baseball without numbers being at the forefront. From batting average to ERA to home runs, players are judged by statistics. However, numbers and statistics are more involved in the game than ever before. From the executive decisions regarding roster construction to coaches’ decisions, analytics are involved in baseball more than anyone on the outside knows. Baseball is truly a numbers game.

Leave a Reply