By BILLY HEYEN

Tony Fuller turned to Hunter Walsh late in the 2019 state semifinal and asked his McQuaid ace if he could give him an inning. Never in four years had Walsh answered that question in anything but the affirmative.

“I was like, ‘I don’t want to rush anything,’” Walsh said. “Ryan (O’Mara’s) in his groove, I was like, ‘You know what? No. I’m not doing it.’”

Moments later, after O’Mara’s nail-biting escape to advance to the next day’s final, Fuller put on a confident face for the media, happy that he’d have his star right-hander the next day. Internally, his mind was spinning, wondering who he could start if Walsh was unavailable.

“I was saying that because we didn’t want to give any inkling that he was hurt,” Fuller said, “but I didn’t think (Walsh) would go.”

The rest, as they say, is history. Walsh took the ball on Saturday, June 15, 2019, threw 70 pitches, walked one batter and allowed no hits. A no-hitter in the Class AA state final was improbable enough, but it came from a pitcher who could barely raise his right arm above his head earlier that week.

“You can’t write this stuff,” Walsh’s catcher, Ben Beauchamp, said. “If you watched that in a movie, someone’s gonna say, ‘All right, that’s a little corny.’”

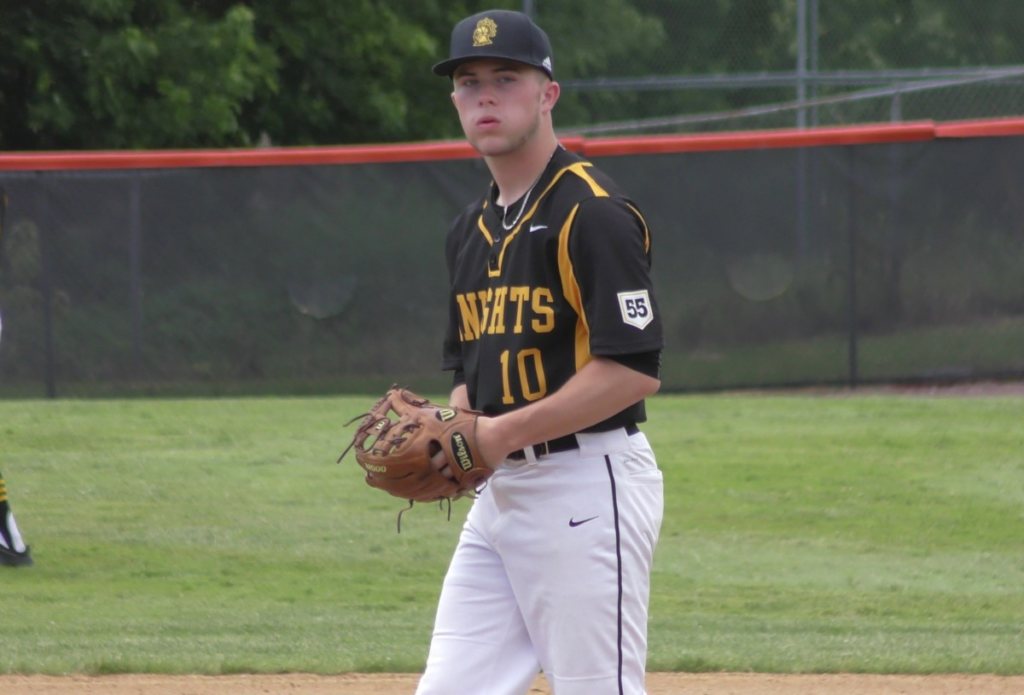

Walsh was McQuaid’s ace the entire season. He won the sectional final and Far West Regional for the Knights with complete game victories. He finished the 2019 season with a perfect 12-0 won-loss record and an ERA below 0.60.

But in the minds of Walsh and his fellow seniors, their final campaign was always about earning state championship rings.

“Obviously we didn’t know what we were gonna do,” shortstop Noah Campanelli said, “but we had such a promising group and the goal always was from day one, win that state championship.”

There’s no telling what would’ve happened if Walsh hadn’t been able to pitch on the final day of the season. A high-powered McQuaid order might’ve gotten the job done anyway, or maybe an underclassman pitcher would’ve stepped up. There certainly wouldn’t have been a no-hitter.

A year later, this is a look back at the week that led to such a monumental feat: The time with a trainer, the uncertainty, the pain and one remarkable line of foreshadowing that led to one of the greatest pitching performances in New York state history.

“I did everything in my power,” Walsh said, “every single day that whole week to try to put myself in that position where I was able to pitch one last time for the great school of McQuaid and do something special with a team I love playing with.”

More: Read the game story from McQuaid’s state title here

Worse than expected

Walsh’s postseason already verged on the stuff of legend before the state final four. He’d started three times, allowing two runs total and striking out 31 batters across three seven-inning complete games. He’d pitched 65 innings so far in the spring, usually approaching the pitch-count limit as a power pitcher with 100 strikeouts on the year up to that point.

There’d never been any arm pain that was out of the ordinary though, nothing beyond the usual post-start soreness. And Fuller called Walsh one of the hardest working pitchers he’d ever coached, with the four-year varsity righty never failing to get his post-start workouts in.

“The last two games (Walsh) pitched, it was almost like we had so much confidence coming out of that with Ryan and the way Hunter’s pitching,” Campanelli said. “We got a real shot to win.”

There wasn’t any unusual soreness after Walsh threw 128 pitches in the sectional final win over Penfield, getting the final out against the final batter he was eligible to face. But after his Far West Regional victory against Frontier, Walsh’s arm felt different.

The Knights had a workout the following day, and Walsh noticed that he couldn’t bench press the same weight he normally could. At Monday’s practice, he loosened up his arm the same way he normally did, shaking his arm and wrist back and forth while holding his glove. That felt fine.

When Walsh picked up a baseball and threw it, though, he felt something “catching” in his right shoulder. He heard a click, too. So he shut it down for Monday.

“He wanted to get on that mound, so he didn’t really let anyone know,” third baseman Tyler Griggs said. “It was kind of suspicious. We were like, ‘Yo, are you OK?’ He was just like, ‘No, but it doesn’t really matter.’”

The pain and the clicking sound didn’t go away basically the whole week, so Walsh didn’t throw. Not his usual flat-ground sessions or a short bullpen or even much longer than testing the arm out to 60 feet before deciding to shut it down each day.

“At first it was kind of scary,” Walsh said. “It was like, wow, this really had to happen right before we went to states… It was a really bad feeling at first.”

All Walsh’s efforts went into finding a way to get his arm ready for the weekend. In his mind, he was going to start Friday, no matter what it took. Stretching, arm circles, band work, massages, ice, heat, Advil, anything and everything he and McQuaid’s trainer could think of.

Even after the fact, Walsh never had an official diagnosis on his shoulder. He took two weeks off after the state final, then when he picked up a football to prepare to quarterback St. John Fisher in the fall, the pain of that final baseball week was gone. All Walsh knew in the final week of his high school baseball career was that he couldn’t throw, but he had to.

“We’re days away from the state championship, and a couple times I saw him pick up a baseball, throw a couple times and then just shut it down,” Campanelli said. “It was kind of apparent to everyone. It was kind of looming over us, and it was scary.”

He has to pitch, right?

When McQuaid’s other players talk about Walsh, even a year later, they often arrive at a common way to describe him: “He’s a dog.”

To them, that means Walsh is a competitor. He’s a fighter. He’s going to work through whatever issues he may have on a given day to give the Knights everything he has.

So even when Walsh spent the majority of practice time in last season’s final week not throwing and instead with a trainer, his teammates didn’t see a reason to worry. Nothing would keep Hunter Walsh from taking his spot on the mound at the state final four, would it?

“I know Hunter as a kid,” second baseman Zach Lee said. “He’s not gonna sit out and pout about his arm. He’s a big kid. He can play.”

The biggest thing that worried a few of the Knights that week, Beauchamp said, was that Walsh “wasn’t making any progress.” A day or two of rest didn’t suddenly restore all his arm strength.

O’Mara, Walsh and Fuller spoke multiple times that week, with Fuller essentially telling his two starters to be ready when he needed them, then pulling O’Mara to the side and confirming it was his ball if Walsh couldn’t go Friday. Beauchamp could sense by Wednesday that Walsh definitely wouldn’t be ready to throw Friday.

“I’m not gonna lie,” Beauchamp added, “after about Wednesday or Thursday, I really didn’t think he was gonna be able to throw on the weekend.”

Fuller didn’t want to rush any decisions ahead of Friday’s state semifinal. With a deep roster, all the McQuaid pitchers not named Walsh took part in their usual between-outing routines. O’Mara hadn’t pitched since May 30’s sectional semifinal, making the gap between that and the state semis his longest time off of the season. But flat ground work and about three 30-40 pitch bullpen sessions each week kept him sharp.

McQuaid was going to see how Walsh felt on Friday in pregame warmups to 100 percent lock in its decision. But on the lineup card Fuller wrote up Thursday night, he put a ‘1’, to designate pitcher, next to O’Mara’s name.

“It was basically let’s get through the semifinal with O’Mara and see what Hunter can give us in the championship,” Fuller said, “and if he can’t give us anything, we piece it together.”

The last night

After O’Mara pitched McQuaid into the state final, everything shaped up perfectly from an outsider’s perspective: Fuller had apparently gambled in saving his ace for the final, and it worked. But all the Knights knew was they weren’t quite sure what Walsh could offer Saturday.

With the state final slated for 10 a.m. Saturday morning, that left about 16 hours for Walsh’s right arm to be ready.

“It was all hands on deck,” Fuller said.

Back in Walsh’s hotel room, where he roomed with Beauchamp for the weekend, Walsh didn’t want to think negative thoughts. His four-year varsity career couldn’t have been scripted for a better ending, aside from his arm issues. So the arm needed to not be an issue any longer.

That meant Walsh went through that week’s routine one final time. The stretching and ice and heat and Advil. The massage that night was the longest of the week, more than half an hour as McQuaid’s trainer did what he could.

“I kid you not, a half hour, 45 minutes just sitting there digging my arm out,” Walsh said of the massage, “digging my bicep out, just getting my forearm right, stretching it out, making sure I can freely move around with no pain.”

The expectation in the rest of McQuaid’s hotel was that Walsh would step on the mound Saturday to start the state final. There was uncertainty, sure, but because of how Walsh had handled himself all week, many of the players weren’t quite sure how bad it was. Even with their belief in Walsh, though, they didn’t know if a fourth-straight postseason complete game was in the cards.

Fuller’s mind hadn’t stopped spinning since the semifinal’s final out. The two options he’d arrived at were sophomore Maxwell Stuver and freshman Will Taylor. Fuller figured he’d go with the southpaw Taylor if Walsh couldn’t go.

“Our offense was so dominant,” Lee said, “if he doesn’t pitch all that well, all these championship games we’re putting up seven-plus runs, five-plus runs. When every kid in your lineup can go yard on the pitcher, I think everyone’s pretty confident.”

If the rest of the Knights could’ve heard what Walsh said at the conclusion of his massage, their worries may have been eased even more. For the first time all week, Walsh’s arm felt a bit more like itself. So he stood up, with the trainer present along with Griggs and Beauchamp, and uttered a sentence of foreshadowing nearly too good to be true. The trio of starters remember the line a bit differently, but the message was the same.

“I looked at Ben, jokingly,” Walsh said, “and was like, ‘I might as well go out there and throw a no-hitter tomorrow.’ I haven’t felt this good this whole week.”

“Hunter stands up and word for word, he says, ‘I’m gonna throw a no-no tomorrow,’” Beauchamp remembered.

‘Perfect timing for it’

Walsh, who’d grown up a dominant force in Penfield’s Little League, had never thrown a no-hitter in his life before the state final. The way he did it that day wasn’t how the rest of his postseason starts had gone, either.

He still pounded the outside corner the way he always did. From the outset in the final, he showed that pitch wouldn’t be a problem. But instead of racking up strikeouts, he piled up quick outs. The first two innings, Walsh threw nine pitches apiece. His arm felt “different,” “weird” after not having thrown all week. But those quick innings brought a sense of relief all around the diamond that McQuaid’s ace had his good stuff.

“Hunter went in and he went 1-2-3,” Griggs said, “and I just remember he got the last kid out of the inning and he counted 3 on his fingers and hushed the dugout or something like that, and the ump yelled at him or something. I was like yeah, there is no way that we are losing this game.”

For the majority of the game, the Knights weren’t thinking about the zero in Shenendehowa’s hit column. This was the state final. They just wanted the ring they’d chased all season.

But they began to notice in the fifth and sixth inning. No one mentioned it, of course — that’s a baseball taboo. Walsh only started to realize when everyone in the dugout avoided talking to him between innings.

It was made all the more surreal for those in McQuaid’s dugout, those who knew Walsh had been dealing with an arm injury, when they watched him get his arm shaken out between each inning. It was a perfect game until the sixth, too, when Walsh lost a 3-2 fastball just a bit low and outside.

“If I knew that that was gonna be the only pitch that was gonna mess up a perfect game, yeah I wish I had a couple inches more inside on that,” Walsh said, laughing. “Hey, what are you gonna do, that’s baseball.”

The seventh inning was mostly drama-free, although Walsh said he held his breath on a popup to shallow left before Jack Beauchamp came sprinting on for the inning’s second out. Noah Campanelli fielded the final grounder at shortstop before letting go what he called recently a “lobbed” throw to first. It found Merkley’s glove and all at once, the history was McQuaid’s and Walsh’s.

“Definitely that game, I would give more credit to our defense behind me, they made a lot of tough plays,” Walsh said. “I was able to get a lot of batters to roll over, they were ready for that. We just all came together, and I think that no-hitter speaks for the whole team, not just me.”

The celebration was fragmented for a moment as Walsh broke away from the mound to hug his catcher, Ben Beauchamp. Then they joined in the party near the pitcher’s mound.

On the bus afterward, Walsh’s phone was blowing up. A text from one of his future Fisher football coaches was the first thing that made him realize the magnitude of what he’d just done.

“That was easily one of the craziest sports moments that I’ve ever witnessed,” Beauchamp added. “He thought going into the game, even with a dead arm, he thought maybe we could get a good four innings out of (him). The kid goes a full seven, doesn’t let any hits up.”

After the state championship’s final out, Merkley made sure to give Walsh the baseball. It wasn’t the only ball used that day, but it’s the one that Campanelli tossed across to first for the no-hitter and the state title.

Walsh still has the ball, and unlike the state championship ring which he’s yet to wear, the baseball makes its way outside occasionally. It sits in the glove Walsh wore in the state final, a glove he didn’t use in his freshman baseball season at Fisher. But once in a while, Walsh meets up with O’Mara for a game of catch with the historic baseball, which “brings back good memories,” Walsh said.

“I think it’s something that people should remember,” Walsh said. “We had a pretty special group, a great group of guys, and I wouldn’t trade any of that away for the world.”

Leave a Reply